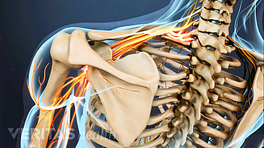

Before beginning manual therapy or any type of physical therapy, the practitioner usually performs a full assessment of the blood and nerve supply in the area, as well as a bone and muscle assessment, in order to decide whether or not there is an increased risk of complications from the use of these back pain management techniques. Depending on the results of that assessment and each individual back pain patient's particular situation, the healthcare provider may perform some or a combination of the following types of manual physical therapy:

Soft Tissue Mobilization

It is important to recognize the role of muscles and their attachments around the joints. Muscle tension can often decrease once joint motion is restored, but many times the spasm will continue to be present. In such cases, muscle tension should be addressed or the joint dysfunction may return. The goal of soft tissue mobilization (STM) is to break up inelastic or fibrous muscle tissue (called 'myofascial adhesions') such as scar tissue from a back injury, move tissue fluids, and relax muscle tension. This procedure is commonly applied to the musculature surrounding the spine, and consists of rhythmic stretching and deep pressure. The therapist will localize the area of greatest tissue restriction through layer-by-layer assessment. Once identified, these restrictions can be mobilized with a wide variety of techniques. These techniques often involve placing a traction force on the tight area with an attempt to restore normal texture to tissue and reduce associated pain.

Also see The Graston Technique: An Instrument Assisted Soft Tissue Manual Therapy for Back Pain

Strain-Counterstrain

This technique focuses on correcting abnormal neuromuscular reflexes that cause structural and postural problems, resulting in painful 'tenderpoints'. The therapist finds the patient's position of comfort by asking the patient at what point the tenderness diminishes. The patient is held in this position of comfort for about 90 seconds, during which time asymptomatic strain is induced through mild stretching, and then slowly brought out of this position, allowing the body to reset its muscles to a normal level of tension. This normal tension in the muscles sets the stage for healing. This technique is gentle enough to be useful for back problems that are too acute or too delicate to treat with other procedures. Strain-counterstrain is tolerated quite well, especially in the acute stage, because it positions the patient opposite of the restricted barrier and towards the position of greatest comfort.

In This Article:

- Manual Physical Therapy for Pain Relief

- Specific Manual Physical Therapy Techniques

Joint Mobilization

Patients often get diagnosed with a pulled muscle in their back and are instructed to treat it with rest, ice and massage. While these techniques feel good, the pain often returns because the muscle spasm is in response to a restricted joint. Joint mobilization involves loosening up the restricted joint and increasing its range of motion by providing slow velocity (i.e. speed) and increasing amplitude (i.e. distance of movement) movement directly into the barrier of a joint, moving the actual bone surfaces on each other in ways patients cannot move the joint themselves. These mobilizations should be painless (unless the operator approaches the barrier too aggressively).

Muscle Energy Techniques

Muscle energy techniques (METs) are designed to mobilize restricted joints and lengthen shortened muscles. This procedure is defined as utilizing a voluntary contraction of the patient's muscles against a distinctly controlled counterforce applied from the practitioner from a precise position and in a specific direction. Following a 3-5 second contraction, the operator takes the joint to its new barrier where the patient again performs a muscle contraction. This may be repeated two or more times. This technique is considered an active procedure as opposed to a passive procedure where the operator does all the work (such as joint mobilizations). Muscle energy techniques are generally tolerated well by the patient and do not stress the joint.

High Velocity, Low Amplitude Thrusting

The goal of this procedure is to restore the gliding motion of joints, enabling them to open and close effectively. It is a more aggressive technique than joint mobilizations and muscle energy techniques that involves taking a joint to its restrictive barrier and thrusting it (low amplitude of less the 1/8 inch) to, but not past, its restrictive barrier. If utilized properly, increased mobility and a decrease in muscle tone about the joint should be noticed. This technique is utilized for restoration of joint motion and does not move a joint beyond its anatomical limit. Therefore, no structural damage takes place and the patient should not have an increase in pain following the treatment.

See Spinal Manipulation: High-Velocity Low-Amplitude (HVLA)

Maintaining Back Pain Relief Long-Term

To continue the healing process and prevent recurring pain, back pain patients are encouraged to engage in other appropriate treatments (including an exercise program) during and after manual therapy treatment. Exercise programs for back pain usually include stretching and strengthening exercises and low-impact aerobic conditioning, and should include a reasonable maintenance exercise program for patients to do on their own. The goal is to maintain the right type and level of activity to prevent the pain from re-occurring and avoid the need for frequent return visits to the therapist.