Lyme disease is commonly associated with tick bites and a big circular rash. However, a tick bite does not hurt and many people do not recall being bit or seeing the rash. Further complicating matters, Lyme disease symptoms may start out minor and not become problematic for months or longer.

Media reports rarely focus on neck pain with Lyme disease, but some estimates note that it occurs in more than 30% of the cases and is typically one of the earlier symptoms. 1 Lyme disease and symptoms. Johns Hopkins Arthritis Center Web site. https://www.hopkinsarthritis.org/arthritis-info/lyme-disease/lyme-signs-and-symptoms/. Updated March 27, 2012. Recognizing Lyme disease early and seeking treatment can make a big difference in the outcome.

In This Article:

Common Symptoms

As Lyme disease advances, it may lead to the development of a stiff neck.

Most early symptoms of Lyme disease—such as fatigue, fever, chills, headaches, and/or joint and muscle aches—are similar to numerous other conditions. Perhaps the most distinguishing early sign of Lyme disease is the big red rash (about 2 inches or more in diameter) that might develop at the tick bite site 3 to 30 days after the occurrence. Normally the rash is visible within 7 days and may look like a target or bullseye. 2 Signs and symptoms of untreated Lyme disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Website. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/signs_symptoms/index.html. Updated October 26, 2016. However, not everyone with Lyme disease gets a rash, and some people who get the rash might not notice if it is located out of sight, such as on the back.

If Lyme disease progresses, a painful and stiff neck can develop. Some people with Lyme disease have even reported a stiff neck as their first noticeable symptom.

Other symptoms of Lyme disease that can potentially develop later include:

- Nerve pain. This pain can range from dull to sharp or shock-like. Some examples could include shooting pains in the arm, buttock, or leg.

- Tingling or numbness. These sensations may be felt in various parts of the body, but are particularly difficult if experienced in the hands and/or feet, which could cause coordination problems.

- Mental health challenges. The person may experience difficulty with short-term memory, confusion, or become easily agitated.

- Facial palsy. Paralysis of facial muscles could cause drooping of an eyelid and/or cheek, preventing a full smile and possibly causing slurred speech. Facial palsy could occur on one or both sides of the face.

This list covers many of the common symptoms of Lyme disease, but a complete list would be beyond the scope of this article. In addition, Lyme disease is often accompanied by one or more coinfections, such as Babesia and Bartonella. These and other types of infections are also capable of causing numerous symptoms, including neck pain and/or intense neck stiffness.

How Lyme Disease Causes Neck Pain

Lyme disease causes neck pain by infecting muscles, tendons, and nerves, leading to inflammation.

Many aspects of Lyme disease are still not fully understood, including how exactly it causes neck pain and stiffness. However, it is thought that the primary bacteria of Lyme disease in the United States, Borrelia burgdorferi, can get into tendons, ligaments, muscles, intervertebral discs, blood vessels, and/or the linings of nerves—including in the neck—causing inflammation, pain, and muscle spasms.

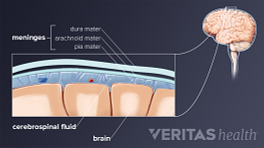

In rare cases, Lyme disease can cause meningitis—inflammation of the protective tissues covering the brain and spinal cord—which can also result in neck pain and stiffness.

See When Neck Stiffness May Mean Meningitis

One animal study linked Borrelia burgdorferi to mast cell activation, and some in the medical community suspect Lyme disease may occasionally cause mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS). 3 Talkington J, Nickell S. Borrelia burgdorferi spirochetes induce mast cell activation and cytokine release. Infect Immun. 1999; 67(3): 1107-15. MCAS is a disorder where the body’s immune system overreacts to various environmental triggers or stress. It can cause numerous symptoms throughout the body and could potentially cause muscle, joint, or bone pain in the neck.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing Lyme disease typically follows this process:

- Patient history and physical exam. The doctor will learn about the patient’s symptoms and when they started. The patient may even remember seeing the tick or a rash.

- Lab tests. If Lyme disease is suspected, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) blood test is given. If the ELISA test is positive, a second blood test, called a Western blot, will likely be done to confirm a Lyme disease diagnosis.

While this process sounds straightforward, in practice it is not so simple. For example, it is possible for a person to have never seen the tick bite or rash, in which case the doctor is far less likely to suspect Lyme disease.

Also, even if Lyme disease is suspected, the blood tests are not always accurate. It is common for someone to have Lyme disease but test negative for it, especially during the first few weeks of the infection.

Treatment

If Lyme disease and its co-infections are caught early, they can usually be treated successfully with antibiotics before serious symptoms, such as neck pain and joint pain, fatigue, and/or neurological problems, become chronic and harder to treat. There is a trend that is becoming more common in which treatment with antibiotics may be recommended if an infection is suspected but lab tests are negative. Some physicians recommend early antibiotic treatment due to the poor sensitivity of the tests and because the sequela of the disease is much worse than the possible negative side-effects of a course of antibiotic care.

In cases where Lyme disease has progressed and symptoms have become moderate or severe, treatment is usually multi-modal, including multiple components of healthy nutrition, supplements, detox regimens, and possibly antibiotics. Long term treatment of Lyme disease, Bartonella and similar infections tends to be controversial in the medical community, and more research is needed in this area.

- 1 Lyme disease and symptoms. Johns Hopkins Arthritis Center Web site. https://www.hopkinsarthritis.org/arthritis-info/lyme-disease/lyme-signs-and-symptoms/. Updated March 27, 2012.

- 2 Signs and symptoms of untreated Lyme disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Website. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/signs_symptoms/index.html. Updated October 26, 2016.

- 3 Talkington J, Nickell S. Borrelia burgdorferi spirochetes induce mast cell activation and cytokine release. Infect Immun. 1999; 67(3): 1107-15.