No single test can definitively diagnose symptomatic osteoarthritis of the spine. The process used to make an accurate diagnosis is as follows:

Interview and History

The doctor interviews the patient to gain an understanding of the symptoms and history. The types of questions include:

- When the symptoms started

- The patterns of neck or back pain and stiffness (e.g. worse in the morning, gets better as I get up and move around)

- What eases pain or makes it worse

Before the doctor’s appointment, you may want to keep a journal to record your symptoms and when they occur.

In This Article:

Physical Exam

The physician evaluates the patient’s overall health and spine. He or she may use some combination of the following tests:

- Visual inspection of the overall posture and skin overlying the affected area

- Hands-on inspection by palpating for tender areas and muscle spasm

- Range of motion tests to check mobility and alignment of the involved joints

- Segmental examination to check each spinal segment for proper motion

- Neurological examination, including tests of muscle strength, skin sensation, and reflexes

Other maneuvers and special tests may be used to help narrow down the source of pain.

Medical Imaging and Lab Testing

If osteoarthritis is suspected, medical imaging and lab testing may be done to confirm the diagnosis and/or rule out other possible causes of the patient’s pain.

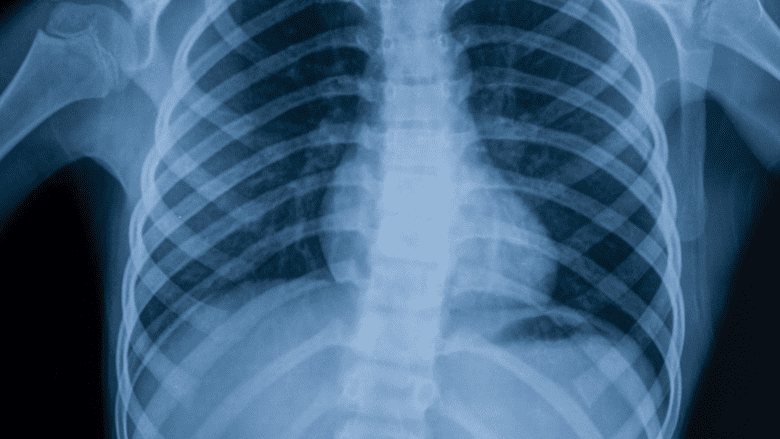

X-rays are helpful in diagnosing spinal arthritis.

X-ray. An x-ray shows signs of degenerative changes in the bones, such as bone spurs at a facet joint, a sign that the bones have tried to compensate for cartilage loss with extra bone growth.

There is a high concentration of nerves radiating from the spine, so even minor cartilage damage or bone spurs detected on an x-ray can translate into a lot of pain if it is in a sensitive spot. It is also possible for a person to experience no pain even though their x-rays to show significant signs of spinal osteoarthritis.

CT scan. A computed tomography (CT) scan may be done to show a cross-sectional view of the spine. For example, CT scans can show whether the spinal canal provides adequate space for the spinal cord.

A CT scan requires a patient to be still for several minutes. One drawback to a CT scan is that it delivers significantly more radiation to the patient than a single x-ray.

MRI Scan. Like CT scanning, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) gives doctors a cross-sectional view of the spine. Unlike an x-ray or CT scan, an MRI does not deliver radiation to the patient; it only uses a strong magnet that provides a detailed look at soft tissues, including vertebral discs, ligaments, tendons, and muscle.

Most MRI scans require the patient to lie flat in a long, narrow tube for 30 to 60 minutes. In some cases, the patient may be standing up, called a stand-up MRI.

SPECT scan. A single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scan, uses nuclear medicine and provides visual images of metabolic functions, such as blood flow. It is often used in conjunction with a CT scan to help narrow down specifically where a problem is occurring in the spine.

Diagnostic injection. A doctor may inject a local anesthetic (and possibly a corticosteroid) into the facet joint or near a nerve that seems to be the source of pain and then observe how it affects the patient’s pain levels. This procedure helps pinpoint the source of pain and can help rule out or confirm certain diagnoses.

The local numbing agent usually numbs the area for a few hours. If complete pain relief is experienced during this time, then the injected area is the likely source of pain.

If there is only partial relief from the local anesthetic, then there may be an additional source of pain. Additional injections or diagnostic studies may be considered.

Lab tests. In some cases, lab tests may be used to rule out other conditions, such as autoimmune conditions, infection, or malignancy.

Lab tests may require a blood draw or an aspiration of the spinal fluid (sometimes called a spinal tap).