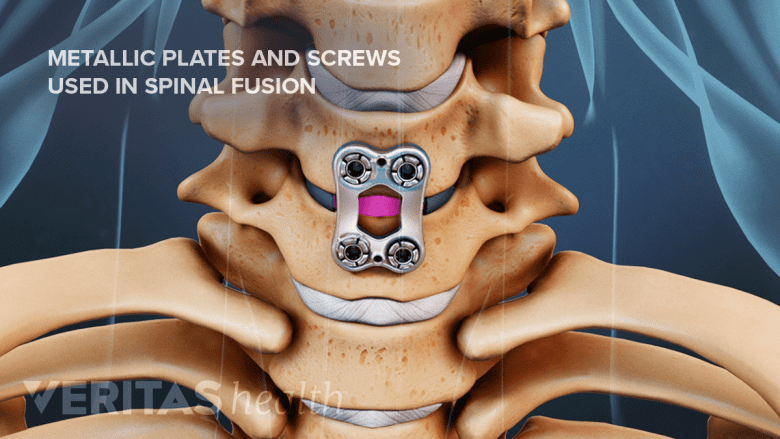

The role of spine fusion instrumentation is to provide additional spinal stability while helping the fusion heal.

Various forms of instrumentation (medical devices) have been developed with the goal of improving the rates of successful spinal fusion. Because bone tends to fuse more effectively in an environment where there is little motion, instrumentation helps the fusion set up by limiting the motion at the fused segment. Instrumentation may also be used to improve spinal alignment or enhance the expansion of disc space (indirect decompression).

In This Article:

- Spine Fusion Instrumentation

- Pedicle Screws for Spine Fusion

- Interbody Cages for Spine Fusion

Why Instrumentation Is Important in Spine Fusion Surgeries

Metal plates and screws stabilize the spine during the fusion process.

The primary purpose of spinal instrumentation is to help improve the overall stability of the spine, correct malalignment, and enhance spinal fusion. To achieve these goals, a range of different types of spinal instrumentation act by:

- Restricting movement in the treated spinal segment to help set up the fusion process

- Serving as a medium to replace the spinal disc and restore the height between the vertebrae

- Securing bone graft material within the interbody space between adjacent vertebrae to allow fusion

Fusion surgeries that do not use instrumentation have a higher risk of failed solid bony fusion (pseudoarthrosis) at the treated spinal segment.1Sonntag VK, Marciano FF. Is fusion indicated for lumbar spinal disorders?. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(24 Suppl):138S-142S. Pseudoarthrosis typically results in an abnormal union of the joint and reduced healing. If pseudoarthrosis occurs, it commonly causes pain at the treated segment and may need an additional fusion surgery for correction.

Read more about Failed Spinal Fusion Surgery

Spine Fusion Instrumentation Types

The type of instrumentation used to fuse a spinal segment is chosen based on the part of the spine that's being treated and the height between the vertebral segment after the removal of the disc. The surgical approach taken to treat the spinal segment also dictates the type and size of the hardware used.

Cervical instrumentation

Most cervical fusion surgeries are performed at or below the third cervical vertebra, C3.2Al Barbarawi MM, Allouh MZ, Qudsieh SM, Barbarawi A. Cervical decompressive laminectomy and lateral mass screw-rod arthrodesis: surgical experience and analytical review of 4120 consecutive screws. Br J Neurosurg. 2021;35(4):480-485. doi:10.1080/02688697.2021.1887450 Cervical spine fusion can take an anterior approach (ACDF), a posterior approach (PCDF), or a combined anterior and posterior approach, and can be performed at multiple levels.

Common tools used to fuse cervical vertebrae may include some combination of:

- Cranial screws-placed at the base of the skull and connected to cervical screws using rods

- Anterior cervical plates with bolts or screws—placed at the front of the vertebrae

- Occipital plates with bolts or screws—placed at the base of the skull

- Interbody cages—used to restore the height of the spinal segment after the removal of the disc

- Standalone cages—anchored into the bones without screws or plates, potentially reducing the risk of postsurgical swallowing difficulties and hoarse voice

- Cervical pedicle screws with rods—placed at the pedicles of the cervical vertebrae (these screws are FDA-approved for spinal surgeries3Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff: Spinal System 510(k)s. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. May, 2004. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/guidance-industry-and-fda-staff-spinal-system-510ks.)

- Cervical lateral mass screws with rods—typically used from C3 to C7 (these screws are commonly used in spinal surgeries, but they are not FDA-approved)

Before screws were introduced for use in the cervical vertebrae, surgeons used stainless-steel wires with bone chips to secure the spinal segments.

While these instruments help fixate the cervical spinal segments, wearing a hard neck brace after surgery is an added measure to ensure successful fusion. The hard neck brace can be replaced with a softer brace after a few days, and the soft brace can be discontinued after a few weeks; however, the screws, rods, and plates typically remain long-term.

Thoracic instrumentation

The upper back region of the spine is not as flexible as the lower back due to the rigid sternum and ribs, but painful conditions, such as disc degeneration and pinched nerves (radiculopathy), may occur in this region, especially in the junction between the thoracic spine and the lumbar spine (thoracolumbar junction). The thoracic vertebrae lie behind the ribcage and vital organs, which means that the best approach to surgery on the upper back is from the back or the side.

Common instruments used in fusing the thoracic vertebrae include some combination of:

- Pedicle screws, with or without rods

- Lamina hooks, with or without pedicle screws

- Interbody cages, made of metal or nonmetal

Cages can be made of titanium mesh or nonmetal expandable material, such as PEEK (polyether ether ketone), carbon fiber, and ceramic.4Krafft PR, Noureldine MHA, Greenberg MS, Alikhani P. Minimally Invasive Lateral Retropleural Approach to the Thoracic Spine for Salvage of a Subsided Expandable Interbody Cage. World Neurosurg. 2020;135:58-62. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2019.12.008

Lumbar instrumentation

PLIF surgery uses cages to fill the disc space with bone grafts, facilitating spinal fusion.

Instrumentation used during lumbar interbody fusion surgeries includes many of the options listed above, such as pedicle screws, rods, plates, and cages. Surgical techniques and approaches in the lumbar spine can also determine the types of instrumentation used.

- Anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) requires cages that are supported by screw-rod constructs or plates.1Sonntag VK, Marciano FF. Is fusion indicated for lumbar spinal disorders?. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(24 Suppl):138S-142S. Cages may be large and angled, helping to ensure the spine’s natural curve.5Sasaki M, Kishima H. [Standard Techniques of Spinal Fusion for Lumbar Degenerative Diseases]. No Shinkei Geka. 2021;49(6):1257-1270. doi:10.11477/mf.1436204512

- Posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) combines the use of cages with pedicle screws and rods.1Sonntag VK, Marciano FF. Is fusion indicated for lumbar spinal disorders?. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(24 Suppl):138S-142S.

- Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) may use spacers that may have a crescent shape and are placed toward the front of the disc space.1Sonntag VK, Marciano FF. Is fusion indicated for lumbar spinal disorders?. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(24 Suppl):138S-142S. (Newer expandable cages may allow adequate restoration of the disc space height, which is comparable to ALIF.)

- Extreme lateral interbody fusion (XLIF) and oblique lumbar interbody fusion (OLIF) allow the placement of a larger cage, making this technique more useful in the correction of scoliosis.6Park SJ, Lee CS, Chung SS, Kang SS, Park HJ, Kim SH. The Ideal Cage Position for Achieving Both Indirect Neural Decompression and Segmental Angle Restoration in Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion (LLIF). Clin Spine Surg. 2017;30(6):E784-E790. doi:10.1097/BSD.0000000000000406

Newer techniques, such as minimally invasive endoscopic fusions, may be performed with some combination of these instruments in approaches that are designed to minimize complications.

Additionally, lumbar interbody fusion can be performed through different approaches, allowing the placement of specialized implants through different surgical techniques. For example, the following devices are used to alleviate symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis (narrowing of the spinal canal in the lower back area):

- X-STOP interspinous device: a spacing block placed between the spinous processes

- Wallis device: a spacer held in place with artificial ligaments wrapped around the spinous processes

The lumbar spinal canal narrows slightly when the spine extends backward, and these devices work by preventing the full extension of the lumbar spine.

Potential Risks of Spine Fusion Instrumentation

Persistent post-surgery back pain might necessitate assessment of fusion instrumentation.

In rare cases, the spinal instrumentation used to secure the spinal segments during a fusion surgery may fail to provide the stability and environment favorable for a successful fusion, resulting in potential complications and risks. These risks include, but are not limited to:

- Adjacent segment degeneration. Fusion of a spinal segment and the attached hardware may alter the biomechanics of the spine and cause the load to be re-distributed to the adjacent segments, leading to faster wear and tear. This process may lead to degenerative changes in the spinal segments directly above and below the fused segments.

- Pain. Back pain that does not resolve after surgery may be a reason to re-evaluate the placement of the hardware and may require a possible revision surgery.

- Nerve injury. In rare cases, it is possible that the hardware may be irritating nearby nerves or putting the spinal cord at risk of injury.

- Infection. Infection caused by surgical instrumentation may trigger new back pain after surgery. In some cases, the infection is hidden (indolent infection) and not revealed until a culture is performed on the instrumentation during surgical removal.

- Hardware failure. Hardware used in spine fusion may break from lifting a heavy weight or playing sports too soon after surgery. Hardware failure may be discovered shortly after surgery or over time if the fusion is not successful.

- Prominent hardware. Screws may stick out in a small, painful bump under the skin. This complication can arise after a period of time if the hardware used in surgery shifts or becomes loose.

Additional complications such as blood clots in the lung (pulmonary embolism) and leaking cerebrospinal fluid may be related to pedicle screws.7Takahashi S, Kitagawa H, Ishii T. Intraoperative pulmonary embolism during spinal instrumentation surgery. A prospective study using transoesophageal echocardiography. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(1):90-94. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.85b1.13172,8Nowak R, Maliszewski M, Krawczyk L. Intracranial subdural hematoma and pneumocephalus after spinal instrumentation of myelodysplastic scoliosis. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2011;20(1):41-45. doi:10.1097/BPB.0b013e32833f33d1

When complications arise, hardware removal surgery may be recommended but may not provide complete relief of pain. Research suggests that less than half of patients that reported pain after spine fusion found relief after removing the hardware.9Alpert HW, Farley FA, Caird MS, Hensinger RN, Li Y, Vanderhave KL. Outcomes following removal of instrumentation after posterior spinal fusion. J Pediatr Orthop. 2014;34(6):613-617. doi:10.1097/BPO.0000000000000145 On average, hardware removal surgery due to complications takes place nearly 3 years after spine fusion surgery.9Alpert HW, Farley FA, Caird MS, Hensinger RN, Li Y, Vanderhave KL. Outcomes following removal of instrumentation after posterior spinal fusion. J Pediatr Orthop. 2014;34(6):613-617. doi:10.1097/BPO.0000000000000145

Surgery to remove instrumentation is typically shorter than the original surgery. The surgeon will enter through the same incision, remove any scar tissue, and partially or completely remove the hardware. In cases where fusion is not successful or complete, the hardware may need to be replaced.

- 1 Sonntag VK, Marciano FF. Is fusion indicated for lumbar spinal disorders?. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(24 Suppl):138S-142S.

- 2 Al Barbarawi MM, Allouh MZ, Qudsieh SM, Barbarawi A. Cervical decompressive laminectomy and lateral mass screw-rod arthrodesis: surgical experience and analytical review of 4120 consecutive screws. Br J Neurosurg. 2021;35(4):480-485. doi:10.1080/02688697.2021.1887450

- 3 Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff: Spinal System 510(k)s. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. May, 2004. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/guidance-industry-and-fda-staff-spinal-system-510ks.

- 4 Krafft PR, Noureldine MHA, Greenberg MS, Alikhani P. Minimally Invasive Lateral Retropleural Approach to the Thoracic Spine for Salvage of a Subsided Expandable Interbody Cage. World Neurosurg. 2020;135:58-62. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2019.12.008

- 5 Sasaki M, Kishima H. [Standard Techniques of Spinal Fusion for Lumbar Degenerative Diseases]. No Shinkei Geka. 2021;49(6):1257-1270. doi:10.11477/mf.1436204512

- 6 Park SJ, Lee CS, Chung SS, Kang SS, Park HJ, Kim SH. The Ideal Cage Position for Achieving Both Indirect Neural Decompression and Segmental Angle Restoration in Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion (LLIF). Clin Spine Surg. 2017;30(6):E784-E790. doi:10.1097/BSD.0000000000000406

- 7 Takahashi S, Kitagawa H, Ishii T. Intraoperative pulmonary embolism during spinal instrumentation surgery. A prospective study using transoesophageal echocardiography. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(1):90-94. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.85b1.13172

- 8 Nowak R, Maliszewski M, Krawczyk L. Intracranial subdural hematoma and pneumocephalus after spinal instrumentation of myelodysplastic scoliosis. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2011;20(1):41-45. doi:10.1097/BPB.0b013e32833f33d1

- 9 Alpert HW, Farley FA, Caird MS, Hensinger RN, Li Y, Vanderhave KL. Outcomes following removal of instrumentation after posterior spinal fusion. J Pediatr Orthop. 2014;34(6):613-617. doi:10.1097/BPO.0000000000000145