The distinctive bone structure and complex movement(s) of the sacroiliac joint are held together and powered by an extensive network of ligaments. The muscles surrounding the sacroiliac joint do not specifically move the joint, but the health of these muscles can influence the stability and motion of the joint.

The joint receives its blood supply from major and smaller arteries and has a wide network of nerves that are pain-sensitive.

In This Article:

- Sacroiliac Joint Anatomy

- Sacroiliac Joint Ligaments and Muscles

- Sacroiliac (SI) Joint Anatomy Video

Anatomy of the Sacroiliac Ligaments

The supporting and stabilizing ligaments of the sacroiliac joint connect the joint in several ways. While several ligaments connect the joint from the front and back, others are present between the joint surfaces, holding them together.

Interosseous sacroiliac ligament

The interosseous ligament is one of the strongest of all ligaments in the body.1Wong M, Sinkler MA, Kiel J. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Sacroiliac Joint. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507801/ It bears significant forces while stabilizing the torso and supporting lower body movement(s).

The interosseous ligament:

- Connects the outer surface of the sacrum (triangular part of the lower spine) to the inner surface ilium (hip bone)

- Receives the greatest stresses of the ligaments associated with the sacroiliac joint.2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6

- Forms the major connection between the sacrum and the ilium.

- Prevents forward and downward movement of the sacrum.1Wong M, Sinkler MA, Kiel J. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Sacroiliac Joint. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507801/

- Protects the joint by preventing excessive backward movement.2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6

The interosseous ligament has several layers. Since the back portion of the sacroiliac joint is not covered by a capsule (as in the front), this ligament helps prevent adverse movements of the joint toward the back.1Wong M, Sinkler MA, Kiel J. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Sacroiliac Joint. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507801/

Superior intracapsular ligament (Illi’s ligament)

This ligament is a small band of fibrous tissue that may not always be present. The Illi’s ligament is thought to be an extension of the interosseous ligament and has little or no mechanical value.2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6

Anterior sacroiliac ligament

The anterior sacroiliac ligament is thin, making it vulnerable to injury and pain.

This ligament, sometimes called the ventral sacroiliac ligament, covers the front of the sacroiliac joint, which includes the articular (joint) capsule that encloses the joint in this area. The fibers of this capsule blend with the joint’s capsule in front and do not provide much support.2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6

The anterior SI ligament is relatively thin, making it uniquely vulnerable to injury and pain.1Wong M, Sinkler MA, Kiel J. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Sacroiliac Joint. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507801/,2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6

Posterior sacroiliac ligament

The posterior sacroiliac ligaments connect the back of the hip bones to the sacrum.

The posterior SI ligament runs along the back of the sacroiliac joint and provides considerable stability.2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6 The ligament connects the back of the hip bones (posterior-superior iliac spine and iliac crest) to the sacrum.

There are two components of the posterior SI ligament:2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6

- Long posterior sacroiliac ligament

- Short posterior sacroiliac ligament

The long posterior sacroiliac ligament undergoes tension during the transmission of forces from the legs to the upper body and vice versa.1Wong M, Sinkler MA, Kiel J. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Sacroiliac Joint. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507801/

Accessory sacroiliac ligaments

The following three accessory ligaments help enhance the stability of the sacroiliac joint1Wong M, Sinkler MA, Kiel J. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Sacroiliac Joint. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507801/:

- Sacrotuberous ligament

- Sacrospinous ligament

- Iliolumbar ligament

The sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments create the greater sciatic foramen and the lesser sciatic foramen.1Wong M, Sinkler MA, Kiel J. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Sacroiliac Joint. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507801/,2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6 The largest nerve in the body, the sciatic nerve, passes through the greater sciatic foramen formed by these ligaments. Trauma to these ligaments, and the consequent inflammation, can lead to sciatic nerve pain, which runs down through the leg along the course of the nerve.

SI Joint Muscles

The quadratus lumborum, psoas, and piriformis are a few examples of muscles that maintain stability in the SI joint.

The muscles around the sacroiliac joint do not specifically power its movements; most of the joint’s movements are facilitated by tension on its ligaments.2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6

The surrounding muscle groups typically play a role in maintaining the stability and function of this important joint.

Anatomically, the SI joint is surrounded by over 40 muscles.2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6 The main muscle groups that affect the SI joint are the:

- Back muscles, such as the erector spinae, quadratus lumborum, and multifidus lumborum.2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6

- Hip muscles, such as the iliopsoas.2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6

- Core muscles, such as the rectus abdominis.2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6

- Buttock muscles, such as the gluteus maximus and piriformis.2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6

- Thigh muscles, such as the biceps femoris from the hamstring group.3Yoo WG. Effects of individual strengthening exercises for the stabilization muscles on the nutation torque of the sacroiliac joint in a sedentary worker with nonspecific sacroiliac joint pain. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27(1):313-314. doi:10.1589/jpts.27.313

When these muscles become tight due to inadequate activity (such as from a sedentary lifestyle), they become shorter, and in turn, cause tension around the sacroiliac joint, making it stiff. Adequately stretching and activating these muscles allows the joint to be flexible and function without pain.3Yoo WG. Effects of individual strengthening exercises for the stabilization muscles on the nutation torque of the sacroiliac joint in a sedentary worker with nonspecific sacroiliac joint pain. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27(1):313-314. doi:10.1589/jpts.27.313

Nerve Supply of the Sacroiliac Joint

The sacroiliac joint receives its nerve supply from spinal nerves L4-S2.

The sacroiliac joint is well innervated, causing considerable pain and symptoms to arise from this region during trauma or inflammation. The pattern of nerve supply can vary among individuals. This variability may also be seen on the right and left sides of the same individual. It is believed that this inconsistency may be responsible for the diverse pattern of referred pain from the sacroiliac joint.1Wong M, Sinkler MA, Kiel J. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Sacroiliac Joint. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507801/,2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6

- The sacroiliac joint receives its nerve supply from the major anterior branches (ventral rami) of the L4 and L5 spinal nerves, superior gluteal nerve, and other major branches (dorsal rami) of the spinal nerves L5 to S2.1Wong M, Sinkler MA, Kiel J. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Sacroiliac Joint. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507801/

- The nerve supply of the sacroiliac joint includes sensory innervation, which means that the nerves conduct pain signals from the joint’s capsule, ligaments, and cartilage.2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6

- The joint’s nerves also possess special receptors called mechanoreceptors. These mechanoreceptors help relay information related to movement and joint position. This information helps to keep the body upright and balanced.2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6

The sacroiliac joint typically contains more pain-sensitive receptors than mechanoreceptors. The most pain-sensitive and highly innervated part of the sacroiliac joint is the cartilage.2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6

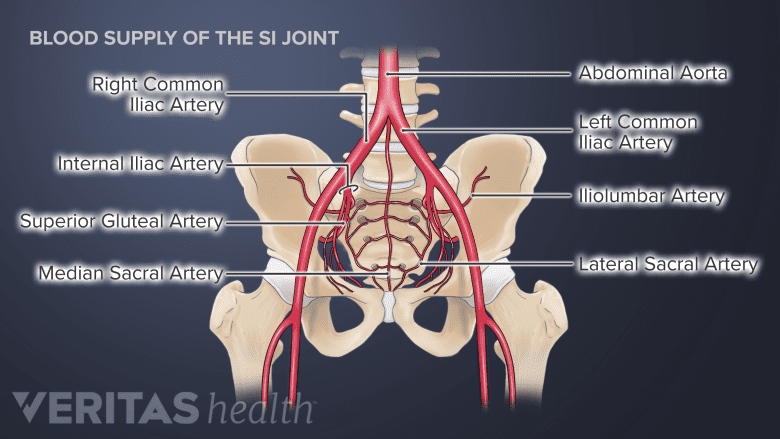

Blood Supply of the Sacroiliac Joint

A vast network of blood vessels supplies the SI Joint.

A rich network of arteries supplies the sacroiliac joint through large and small branches that course along the front and back of the joint.

- The back portion of the joint is supplied by the median sacral artery and lateral sacral artery. Both these arteries arise from the internal iliac artery, commonly found at the spine levels L5-S2. These arteries join with the superficial branch of the superior gluteal artery.1Wong M, Sinkler MA, Kiel J. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Sacroiliac Joint. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507801/,2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6

- The front portion of the joint is supplied by the iliolumbar artery, which originates either from the internal iliac or common iliac artery.1Wong M, Sinkler MA, Kiel J. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Sacroiliac Joint. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507801/,2Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6

The venous drainage of the joint flows into the internal iliac vein.

The vast majority of sacroiliac joint problems affect the joint’s ligaments and/or cartilage. Muscles surrounding the SI joint, such as the back, core, buttocks, and thigh muscles, may also influence the joint if they are tight and not well-conditioned. The joint’s natural development and mechanical loading pattern change with age to accommodate the growing physiological stresses and impacts on the pelvic and hip regions.

- 1 Wong M, Sinkler MA, Kiel J. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Sacroiliac Joint. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507801/

- 2 Cramer, Gregory D., and Chae-Song Ro. "The Sacrum, Sacroiliac Joint, and Coccyx." Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans, Elsevier, 2014, pp. 312–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00008-6

- 3 Yoo WG. Effects of individual strengthening exercises for the stabilization muscles on the nutation torque of the sacroiliac joint in a sedentary worker with nonspecific sacroiliac joint pain. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27(1):313-314. doi:10.1589/jpts.27.313